Northern Ireland centenarian Dave Mullin one of the last men standing from infamous World War Two battle

Having been born on Christmas Day just after the First World War ended, the signs were that Dave Mullin would go on to lead a life less ordinary.

Along the way he survived one of bloodiest battles of WWII and last year Dave reached the age of 100.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWhile he professes that his body is failing him, having spent a few hours at his home in Omagh I can attest that his mind and sense of humour remain sharp as a tack.

However Dave, who has lived in Omagh since 1949, doesn’t see himself as anything special.

His story comes with a disclaimer: “I don’t have a big fancy story to tell about the war. Anybody who tells those sort of stories weren’t there. When you were in the middle of it, it was chaos. You could hardly see in front of you. You could be shot in a second.”

At the age of 25, Dave was at Monte Cassino, one of the most infamous battles of WWII – the 75th anniversary of which took place on Saturday. His brothers Charlie and Tom also fought in World War Two, though not all of them made it home.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe family came from Monaghan, with Dave being born before Northern Ireland even existed.

When the Second World War began, Dave and his brothers were working in England: “We were building things – airfields, oil refineries – everything was geared to war. It was virtually starvation in Ireland at the time, things were in a terrible way.

“We were called up and we decided just to go with it.

“Charlie went into artillery, I went into the infantry. I was with Lancashire Fusiliers and later on was transferred to the North Irish Horse.

“Tom went into the Border Regiment and unfortunately they turned into part of the 1st Airborne Division.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdDave’s brother Tom lost his life in the invasion of Sicily on July 10, 1943.

“Three brothers went out and two came home,” said Dave poignantly.

Dave said that he was handy with firearms, but his skills were not called upon, which he comments was ‘maybe for the best’.

He said: “When I was in the infantry I was a very good shot. I was the best in the company. There were four companies and the best shot from each company went on a course in small arms, transmortars and so forth. We fired everything.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“When the time came they broke the regiment up and transferred us in sixes and sevens to reinforce existing units. I was one of six people sent to the North Irish Horse (a yeomanry unit raised in the northern counties of Ireland). That’s how I got to Monte Cassino.”

Dave said: “I’d fired all these guns. I was a crack shot and from I went to the North Irish Horse I never fired a shot in anger at anybody. Maybe that was lucky, maybe for the best.”

The Allies fought fiercely against German troops occupying formidable defences, suffering heavy losses at Monte Cassino.

After the Allies captured the town of Cassino and the mountain which overlooked it, the Germans retreated north and in June 1944 the Allies went on to liberate Rome.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdTens of thousands of Allied soldiers fought four separate battles at Cassino between January and May 1944 in the shadow of Monte Cassino, where an ancient monastery had been fortified by Germans.

Sharing what he remembers of the Battle of Monte Cassino, Dave said: “It was a long fought out battle up to reach Monte Cassino, the Germans were very determined to hold it.

“I was given the job of supplying 15 tanks with ammunition, petrol and small arms. That was easy enough but very dangerous.

“I never got a scratch. I had fought Russian roulette with Messerschmitts (German aircraft) and got away unharmed.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“My worst moment was when myself and a sergeant were waiting with a loaded vehicle. It was a great vehicle, a box pick-up, bullet-proof wherever it was cladded.

“We got the call for ammunition for a tank. We went in there not knowing where we were going. We went down the side of this farmer’s field. A dispatch rider came out on a motorbike and as soon as he hit the trail some missile hit him and he was immediately swept away. We speeded on and reached the place we were meant to be, delivered the ammunition and got out of there to reload again if needs be.

“Of course the breach was made and we weren’t back at that front again.”

He added: “We knew [the Battle at Monte Cassino] was going to be horrible because the Germans were very determined to hold it.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“It was farmed fields, but it was dry. You weren’t in mud. You could drive almost anywhere in the vehicle. It had four wheel drive and a split gear box.

“We were only at Monte Cassino for two or three days. The battle, the breach only lasted half a day.”

One particular memory Dave has of Monte Cassino is a moment where he could have lost his life: “I remember passing the ammunition into the tank, we were in a line, you took two steps then went back.

“The old sergeant major we had appeared on the scene, he came into the line to shorten it a bit. I let him in on the left. If I’d let him in on the right I wouldn’t be talking to you today.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“This Nebelwerfer shell came over and virtually stripped him of his clothing.

“We retreated and we weren’t back up to the front again except to see the bodies prepared for burial. A lot of my friends died there.

“The next day we were on our way again heading for Rome.”

Dave said the journey from Cassino into the north of Italy was about 700 miles: “It was a day at a time, you moved up bit by bit from one little station to another.

“You might stay somewhere for 24 hours, the next might be three days, bringing stuff to people who were in the front.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“We didn’t see anything like Monte Cassino again. It was bits and pieces.

“We eventually reached Vienna as part of the Occupational Forces from 1945 into 1946. The Russians and the French were there. We lived in the local barracks and everything was fine.

“We saved up our chocolate for months to give the children of Vienna a Christmas party. They gorged themselves with all these goodies, I hope they weren’t sick.”

War is over

Dave told of the moment he learnt WWII was over.

“We found that we could get the BBC World Service in 1943,” he said.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“This station told the truth no matter what. I found by moving the dial about half an inch I could get it, not everywhere but in most places. They read at dictation speed and I wrote down everything and posted it in certain places for the boys to read. We weren’t supposed to listen in but they never charged anybody with doing so.”

He continued: “The news came in that the Germans had surrendered in Italy. I went and told the officer in charge of our unit what I had heard. He said it won’t take long to find out. By this time it had got to the tanks and they were firing shots into the Adriatic, that was it. It was a relief.”

Dave (pictured back right in Rimini after the war was over) was called into the Army on July 24, 1940 and was discharged on July 24, 1946 – exactly six years’ service.

He said: “It’s incredible what people came through, how they survived. The conditions people lived in, the food rationing, the war going on around them.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAfter the war he returned to live in Omagh where he had a friend named Waterson. He joined the civil service and worked in the Department of Agriculture based in Crown Buildings in Omagh.

Centenarian

Dave Mullin reached his milestone 100th birthday on Christmas Day last year.

He said: “I’m 100 plus nearly five months.

“I do feel my age. My legs, ankles, knees are rheumatic. I’m not so good on my feet.”

While Dave was in great form while we spoke it was clear that reaching 100 is not without its drawbacks, particularly in terms of loneliness.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe said: “I’ve no family left except for a few nieces and nephews and their children. They do visit often but some of them have moved away and live all over the world.”

Talking about his nephews and nieces and great nephews and nieces he is clearly very proud of them and keeps a close track of their achievements.

He continued: “My wife Elsie died 20 years ago. She was Omagh born and bred.

“We married in 1957. We had no children, we married a bit late.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“All my very close friends are dead now. It can get a bit lonely.

“I was very friendly with a few of the neighbours. They’ve moved away, but they stay in touch.”

Asked how he likes to spend his time, Dave said: “At 100 what do you do? You do the best to stay alive.

“I live here on my own. Mrs Duffy would come in and straighten things out and straighten me out. She’s wonderful. Her husband is wonderful too. He would give me lifts for hospital appointments.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAt the age of 100, Dave still holds a driving licence and occasionally takes his vehicle for a spin, circumstance allowing: “I can still drive, but I don’t very often.

“I’d sometimes take a drive out into the country. I can only go somewhere if I’m sure of a parking space. I can’t walk very far.”

Asked if there were any secrets to reaching 100 he said: “There are no secret to long life. More and more people are getting to 100.

“It’s like the four minute mile, it’s probably three and half minutes now.

“I’m very lucky. I’m on my second pacemaker.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOf his sporting prowess, Dave said: “I was quite a good golfer and quite a good dart player. Anything you needed an eye for. I didn’t take up golf at Newtownstewart until I was 41 but I got down to a nine handicap.”

Anniversary

Saturday marked the 75th anniversary of the Battle of Monte Cassino – a key turning point in the Second World War

The Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) and the British Embassy in Rome paid tribute to those who fought in Italy with a special ceremony hosted at Cassino War Cemetery – the final resting place of over 4,200 Commonwealth servicemen – on Thursday.

The event was attended by war veterans from the UK and New Zealand, Sir Tim Laurence, Vice-Chairman of the CWGC and UK Minister for Defence and People, RT Hon Tobias Ellwood

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAlthough it was one of the toughest campaigns of the Second World War, the Allied victory was almost immediately overshadowed by the landings in Normandy just two weeks later.

Disparagingly referred to at the time as D-Day dodgers, the servicemen and women of the Italian campaign saw some of the fiercest fighting of the Second World War. The reality of their service and sacrifice is all too evident in the many CWGC cemeteries throughout Italy.

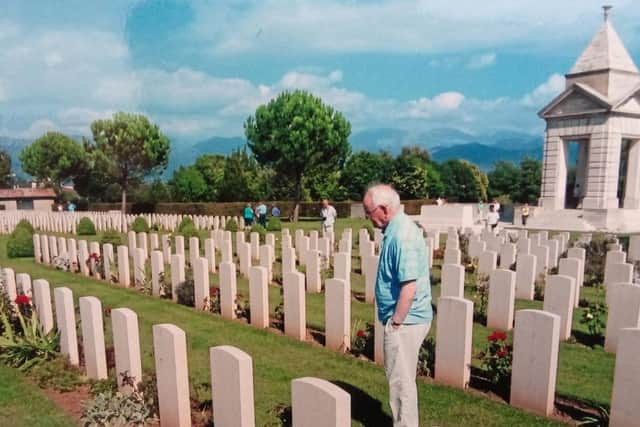

Dave Mullin from Omagh first went back to Monte Cassino in 1959, then again in 1970s, and again in 2009.

He said: “The first time I went back it had just been a ploughed field with a few graves in it.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“I think there’s four and half thousand graves now. It has changed so much.”

The CWGC cares for the graves of over 4,200 Commonwealth servicemen Cassino War Cemetery, most of whom died on the surrounding battlefields. A further 4,000 who died in Sicily and Italy, as well as at Monte Cassino, and have no known grave are commemorated by name on the Cassino Memorial.

The soldiers were drawn from many nations. Alongside the graves of British and Irish troops are Muslims from Indian battalions, Maoris from New Zealand, Canadian and South African servicemen.

Sir Tim Laurence, Vice Chair of the CWGC said: “There are few traces of the Italian battlefields left today but the Commission’s beautifully tended cemeteries honour those who made the ultimate sacrifice in this region, and are a reminder of the human cost of war.”